September 6, 2022

As students return to college campuses this month, many are eager to embark on new research opportunities, or to pick up where they left off last year. Likewise, their research mentors are eagerly anticipating the start of a new academic year. Much of this anticipation is rooted in training the next generation of scientists.

Predictably, anti-animal research groups across the country are capitalizing on back-to-school as an opportunity to promote their extremist views in an effort to gain supporters. These groups, which oppose any use of animals by humans for any reason, are holding events at colleges and universities across the country this week and next. Research institutions must step up.

Back in 2017, we wrote about the obligation of research institutions to publicly support their animal research programs, and to defend the scientists involved against attacks that deliberately misrepresent scientists and their research. We detailed why it is imperative for institutions to speak up rather than leaving the bulk of the defense to individual scientists.

As this academic year gets underway, we underscore that call for institutional action. As we declared at the start of 2022, not only should institutions defend their researchers and animal research programs during such campaigns of misinformation, they should proactively commend their scientists for the invaluable research they conduct. We now specifically call on research institutions to also unequivocally ensure the safety of their scientists, staff, and students.

Openly acknowledging and lauding the research conducted by their faculty, allows institutions to shape the message to its community, effectively thwarting false messaging perpetrated by those fundamentally opposed to animal research. Furthermore, institutions must take proactive steps to ensure research spaces, offices, and classrooms are safe such intruders. Institutions must include scientists every step of the way when responding to attacks from anti-animal research groups. This means including them in discussions about drafting public responses, giving them the option of having a seat at the table when leadership meets with advocacy groups or the attackers themselves, and having explicit protocols in place for when attacks bleed over into scientists personal space — such as, what occurs when activists “doxx” individual researchers or organize protests in their neighborhoods.

As we see anti-animal research groups showing no signs of backing down from their unwarranted assaults, it is increasingly clear that effective, committed, and public support is required from those who have accepted the charge of providing the supportive environment and context for the research.

Research institutions have a moral responsibility to defend their research programs and scientists

Originally posted 9/18/2017

Every university, research institute, company, funder, and benefactor of scientific research that depends on animal studies:

- plays a role in public communication about animal research;

- has a responsibility for provision of responsive, accessible, and useful information about the work, its justification, conduct, oversight; and

- has a moral obligation to defend its science and scientists against attacks that misrepresent them, their research, and the institution’s animal program broadly.

What we have seen and written about over the last decade at Speaking of Research includes nearly everything ranging from institutions-of-no-comment to institutions seriously engaged in proactive, responsive, and genuine public communication about their animal research programs.

What we have not seen is a sea-change in enthusiastic adoption of public engagement by a wide swath of institutions – not only in the US, but also in Asia and some other global regions with significant animal research interest. The reasons for that are neither simple nor mysterious. For one: it is not required, it is not expected, and it is not easy. Nor are its benefits always immediately realized.

Thus, despite the proliferation and growth of industries and professions related to laboratory animal research and compliance over the past decades, we see no evidence of commensurate growth in meaningful, responsive, and inclusive public outreach. We have seen increases in regulatory burden and promulgation of standards sometimes supported by empirical evidence, and other times appearing disconnected from benefit to either animal welfare or science, appearing almost as capitulation to whims and additional rationale to support job creation, expansion of pay-for-certification, and growth of pay-for-accreditation. The situation can lead us to ask whether desire for robotic-like checking of boxes has substituted for real wrestling with moral dilemmas. And we – as a community – can, and should, debate each of those points.

But a probable consensus point is that an expansion of regulatory burden (and accompanying costs) has occurred, a change that is widely thought to be partially influenced by risk aversion on the part of institutions and by the influence of decades of campaigns against animal research. And further, there has been no commensurate change in support for public outreach, public education, and public engagement.

There simply is no regulation, no broad community standard, no pressure, and no consistent encouragement for the scientific community and the institutions in which research occurs to adopt any kind of standard for either proactive or reactive public outreach and education. As a result, the variance ranges from serious, engaged, and responsive public programs to close to nothing at all.

Why does it matter to the public?

There are many reasons that institutions—academic and commercial, public and private– should engage in sustained and serious efforts to communicate fully about their animal research programs. Some of those surround individual principles, goals, and reputations. Some surround the time, energy, and reputational costs of campaigns against their programs.

But what all of them should remember – and what the public should hold them accountable for – is their leadership and contribution to a much bigger picture.

There is no shortage of campaigns against scientific research. That includes studies of other animals, among them biomedical and behavioral science that seeks basic understanding and new knowledge that together are the foundation for advances to benefit society, the health of humans and other animals, and the environment.

Thus, when scientific research and scientists are under attack, it not only scientists, universities, institutions, and funders that are at risk. Rather, it is society at large, the environment, and the global future. Ultimately, it is the public that decides what science should be done, where it is done, how it is funded, and it is the public that shapes the regulatory system under which research is conducted, overseen, and convened.

Individual institutions, companies, and funders decide what it is they will support within their walls or funding mechanisms. Scientists themselves, though, decide whether–or not– they will use their creativity, intellect, training, time, and energy to conduct research, to apply for funding to do so, to continue to invest themselves in addressing questions and producing new knowledge and discoveries.

Simply put:

- Scientists can choose whether, or not, to do science. Whether they do so is affected by many factors. Among them is institutional and societal support, as well as the impact of campaigns against them.

- Institutions can choose whether, or not, to actively and effectively support their research programs.

- The public can choose whether, or not, they want to support science broadly, or support particular avenues for scientific discovery and advances.

But none of these decisions is truly independent, nor are they simple. That is the point. The ability to do science, to engage and retain scientists, and to benefit from science are interdependent in many ways, are complex, and require serious consideration by scientists, institutions, funders, and the broad public. Part of the obligation of research institutions is to contribute to this broader consideration that informs decisions and the future, including the future of their own programs and ability to conduct research.

Why should institutions speak up? Can’t scientists say whatever they want? (also, isn’t it their job?)

Short answer: No.

Although university tenured faculty are fairly privileged with respect to protection of their academic freedom to speak about their scholarly work, many scientists, including those who study animals, are under both implicit and explicit pressure that prevent them from speaking freely or engaging in public dialogue about their work. Imagine that. You’re a university, state, federal, or private employee – a scientist with deep knowledge and conviction about how your research benefits society, about how the nonhuman animal studies are necessary and without alternative – but you are muzzled in the face of campaigns against your work. Obviously, this is a bad spot for the scientist. But you know what?

It is also a bad thing for the public. Why? Because it prevents the public from hearing from the experts in the area. The strength of a democracy relies upon an informed citizenry to make decisions. An important piece of the informed part depends upon having access the full range of information – the knowns, the unknowns, the potential short-term and long-term benefits and risks of a various decisions and courses of action.

When scientists, institutions, and federal agencies fail to contribute their own expertise, they fall short of contributing what is needed to assist effective public decisions. In fact, what we have seen many times is the dominance of campaigns led with loud voices emphasizing only a select set of facts. We see decisions get made that effectively ignore science, ignore its process, and set aside the risks that are associated with failing to conduct particular kinds of scientific research, or address particular kinds of questions.

At the end of the day, the public can decide to ban research in some topics or research with some species. Or, they can impose regulatory and paperwork hurdles that are so high and cause such delays that scientists must choose to do something else. And, of course, public campaigns can result in a such a significant and broad range of harassment tactics that scientists are left little choice but to protect their families, loved ones, and own health – all of which mean changing their research.

None of these outcomes is a victory for the public, for the future, or for science. Few of these are based in serious, thoughtful, fact-informed consideration of the benefits and risks of different courses of action.

All of these issues, however, reflect something that is known quite well by opponents of animal research. Opponent groups need “victories” to provide evidence of their effectiveness to current and potential donors. For some, “victories” are any occasion in which a scientist or a lab appears to cease studies. For others, the metric is the gross number of media stories related to their campaigns. Neither is an outcome particularly well anchored in a public good or a change in animal research.

Given the choice of a publicly open and likely-to-defend-the-work target and one with one or both hands (and mouth tied), an opponent group would just be lacking in savvy to choose the unmuzzled opponent. Conversely, a target with little evidence of proactive public coverage of its animal research and little history of defending its scientists, must appear as perfect game. In many of these cases, it is worth noting that the scientists themselves know how to talk about the work, why it is justified, why it is in the public’s interest, why it has benefit, how the animals are cared for. Why? Because every single one of those points is requisite to grant applications, to IACUC protocols, to scientific publications and presentations. It may be the case that the institution or agency’s press office, administration or IACUC is not able to rapidly articulate those points, but the scientists most often can. That does not mean that the scientist should be the only person talking– it means that they should be both supported and included in public communications.

Why institutions?

Speaking of Research encourages a wide range of people in public education and dialogue about animal research. Public communication, dialogue, and defense of science are close to the heart for many of us. It is also true that for scientists, advocacy is one of many jobs—the first jobs being to conduct science, make discoveries, teach and mentor the next generation, provide a whole range of service to the field and public. At this point in history, it also could not be more apparent that there are urgent and competing needs that we – as scientists and as humans – must be concerned. And so, at this point, it is even more apparent than before that we need more. We need more voices and a change in community-wide approaches in order to meet our collective obligation to the public and the future.

There is a need for every institution, company, funder, and scientific organization to communicate with the public. That communication needs to be embedded at every level. It needs to be valued on par with everything else. And it needs to be distributed across all of the groups that contribute to scientific and medical advances with science that involves other animals. What it does not need is a sole student, sole post-doc, sole scientist, a single or small set of institutions or research areas, taking all the heat, flak, and incoming without the full support and engagement of their institutions and communities. Particularly, without effective, committed, and public support from those who have accepted the charge of providing the supportive environment and context for the research.

There are a lot of battles to fight in science. That goes beyond the topic of the science and beyond research with other animals. Institutions and agencies that support research— contributing to scientific discoveries and advances that benefit society, other animals, and the environment— have an important role to play in defending that work and the people who do it. Failing to do so jeopardizes the science and scientists, but moreover, the public that stands to lose in absence of discoveries and serious, fact-informed consideration of decisions about the work and the future.

Allyson J. Bennett

The opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect those of my employer, the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

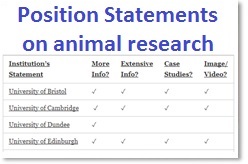

Read more about approaches that universities, companies, and others can take to support pro-active, responsive public communication about animal research:

Discussion about this post